Designed by language experts, Duolingo has a science-based teaching methodology proven to foster long-term language retention. Game-like lessons and fun characters help you build solid speaking, reading, listening, and writing skills.

Whether you’re learning a language for travel, school, career, family and friends, or your brain health, you’ll love learning with Duolingo. Practice speaking, reading, listening, and writing to build your vocabulary and grammar skills.ĭesigned by language experts and loved by hundreds of millions of learners worldwide, Duolingo helps you prepare for real conversations in Spanish, French, Chinese, Italian, German, English, and more.

#SPANISH YO FORMS TO GO FREE#

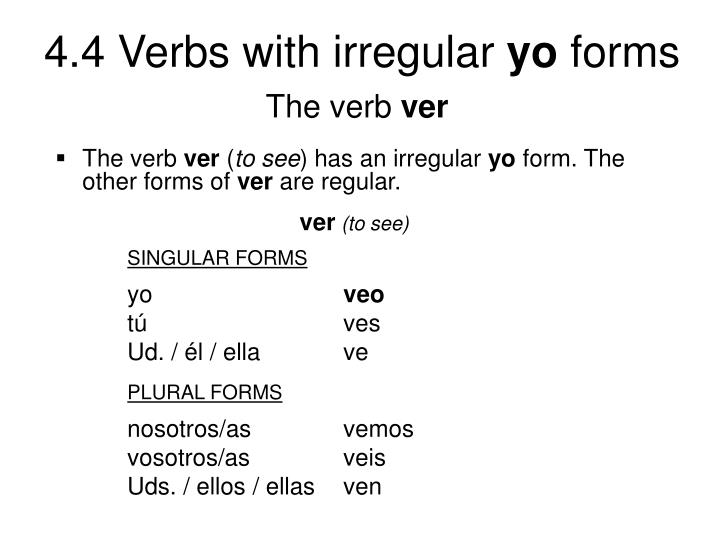

The other irregular yo types - ver, the -oy verbs, and the two -e verbs ( haber and saber) –are another story entirely maybe I’ll post about them later.Learn a new language with the world’s most-downloaded education app! Duolingo is the fun, free app for learning 40+ languages through quick, bite-sized lessons.

#SPANISH YO FORMS TO GO FULL#

You can check my Teaching page for a full list of the -zco verbs. Likewise, the -go pattern spread to other common verbs including venir, tener, and salir, though at the same time, some verbs originally in the -go group became regular ( cocer is one). After these back-and-forths, modern Spanish ended up with almost 100 –zco verbs, and around 10 –go verbs. This was certainly the case with the -zco and -go verbs. The verb lucir and related verbs like deslucir adopted the -zco pattern, as did several verbs ending in -ducir, such as producir, even though none of these had an /sk/ cluster in Latin. The change of /f/ to /h/ in hacer (from facere) is also seen in words like hijo (from Latin filius).Īs I described in an earlier post, analogy untidies the results of sweeping sound changes like these. For example, the /sk/ simplification gave us pez (from Latin pesce), /k/ fronting gave us cielo (from Latin caelu), and /k/ voicing gave us lugar (from Latin locale). (This /g/ is still a lot closer to /k/ than is /s/ or /θ/.) A similar sequence of events impacted Latin dicere as it evolved into decir, giving us the (yo) digo form.Īll the sound changes mentioned above were general, occurring throughout Spanish vocabulary. Later, a separate change voiced the /k/ to /g/, giving us modern hago. Only haco remained in the present tense as a reflection of the original Latin /k/. Only florezco kept the /k/ cluster of the original Latin.įor -go verbs like hacer, from Latin facere, the relevant change was the fronting and softening of /k/ to /s/ or /θ/ before front vowels. So the infinitive changed from facere (with a /k/ sound) to hacer, the tú form to haces, and so on.

So the infinitive changed from florescere to florecer, the tú form from floresces to floreces, and so on. So in this case, everyone else IS wrong, or at least linguistically radical.įor -zco verbs like florecer, from Latin florescere, the relevant change was the simplification of /sk/ to /s/ (in Andalucian and Latin American Spanish) or /Θ/ (in Castilian Spanish) before /e/ or /i/. In a nutshell, their -o ending insulated them from sound changes that affected /k/ before /e/ and /i/ i.e. (This is particularly ironic because Peter didn’t even take Spanish.) It turns out that from a historical perspective, the yo forms are actually the most REGULAR - that is, most faithful to the original Latin.

No Facebook account? Don’t think Seth MacFarlane is funny? Every other “car” in the parking lot is an SUV? Maybe, just maybe…īelieve it or not, I thought of Peter immediately when I looked into the origin of the two biggest Spanish verb groups with irregular yo forms in the present tense: the so-called -zco and -go verbs. In our family, Peter’s quote has become an anti-trend mini-meme. “Maybe, just maybe, everyone else is wrong”

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)